Boston is the World and the World is Boston, the 2025 Foster Prize at the ICA

The community of artists working in the Boston area is not as loud or internationally conspicuous as those in New York or L.A. But that doesn’t mean it's any less vigorous. Boston is home to world-class visual artists innovating across mediums—in sculpture, painting, textiles, installation, photography, print, video and public art. They publish, exhibit, teach and organize. They animate our commonwealth, making it more culturally rich and socially inclusive. And their economic impact is significant. According to the Healey-Driscoll administration, Massachusetts’ creative economy supports about 133,000 jobs and contributes $27 billion annually.

The Foster Prize at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston is the most-high profile and consistent showcase of Boston-area artists in the state. Audrey and Jim Foster, unwavering advocates for the arts, gifted the Prize to Boston in 2006, the same year the museum moved to its new Diller, Scofidio + Renfro building in Fan Pier. The biennial prize gives early and mid-career artists a chance to exhibit in a major museum setting during the busy fall season, promising exposure to new audiences.

This year curator Tessa Bachi Haas selected four artists whose work addresses our current moment in deeply personal and uniquely technical ways. Through their artistic labor, Alison Croney Moses, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Damien Hoar de Galvan, and Sneha Shrestha (aka IMAGINE), resist the negativity and anti-beauty of current political realities, reminding us of the power of art to bring us together, especially when the world seems to want to tear us apart.

“We remain immeasurably proud of the prize. Our goal was to showcase and support Boston artists, and through exposure at the ICA, encourage and incentivize them to build their careers in Boston, rather than chase their dreams in NYC and beyond, (where they could become swallowed up and marginalized). ”

Alison Croney Moses

Alison Croney Moses in her studio. Photo by Yorgos Efthymiadis. Image courtesy of the ICA Boston.

“We have a symbiotic relationship with trees and nature. We’re dependent on them. We have to collaborate, we have to work together.”

For her Foster Prize exhibition, artist and educator Alison Croney Moses created an intricate investigation into relationships and connections—those between people; between natural and human worlds; between ancestors and current selves; and between her material and her body.

Alison Crony Moses, Finding our Lineage series 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Photo Robin Hauck.

Her show consists of twelve curvaceous sculptures made of wood, her primary material. The artist studied furniture design at RISD, and her mastery of woodworking skills and respect for wood’s inherent qualities are felt in every one of her sensuous forms. Best known for her floating, shell-like vessels, she has recently started making denser, partly-painted wall works to push herself into new creative territory.

Croney Moses chose to use walnut in all but two of her Foster Prize pieces, explaining: “[walnut is] deep, beautiful, rich, and layered. I see so many connections to our physical bodies in all wood; I see myself reflected when I look at walnut.”

Alison Croney Moses, Our Unit, 2024. Walnut and milk paint. Photo: Robin Hauck.

Five gleaming, bent-laminate, walnut forms entitled Finding our Lineage 1 - 5 hang from monofilament, like seed pods carrying secrets. Collectively they conjure ideas of Black motherhood, care, privacy and community—core themes in Croney Moses’ oeuvre. She gave these forms an elongated shape, she says, to convey reaching toward a connection to her ancestral past. The artist’s parents are Guyanese, but her upbringing in North Carolina and adult life in Boston have obscured her relationship to her Guyanese roots. She described this series as an early step in her meditation on perceiving those roots more deeply.

The wall works are a study in technical magic. Thin strips of impossibly curvy wood reach away from their glued base to loop and tangle with each other. In Friendships, Wild in One Way and Wild in Another Way (all 2025), milk paint in creamy primary colors draws attention to the curves’ undersides, and the gymnastic complexity of their movements.

Installation view, 2025 James and Audrey Foster Prize, the Institute of ContemporaryArt/Boston, 2025-26. Photo by Mel Taing.

The artist describes working with natural material as a collaboration. She must work in harmony with the wood to get the outcome she wants, just as we must accommodate, adjust, and bend for each other, being careful not to push so hard that we cause someone or something to break.

Yorgos Efthymiadis

Yorgos Efthymiadis by Yorgos Efthymiadis. Image courtesy of the ICA Boston.

“My voice as an artist continues to evolve, as I draw inspiration from the people I photograph.”

The first thing that struck me about photographer Yorgos Efthymiadis’ gallery was its bifurcated design. A dividing wall creates distinct spaces for two series: The Lighthouse Keepers and The First Ones In Line. The artist invites visitors to enter a nook to view his images up close, a thoughtful choice given the nature of his work. Efthymiadis makes tender, often sorrowful images of friends and family at their most vulnerable and resilient, inside the private sanctuary of their homes.

Efthymiadis grew up in Halkidiki, Greece and now lives in Somerville. He began The Lighthouse Keepers in 2019 when he traveled home and discovered he’d lost his connection. “I was feeling banished from my homeland. In a sense, I left everything behind 15 years ago and when I traveled back, it felt like a different place.”

Trained as an architectural photographer, he turned to his camera to find a way back. The Lighthouse Keepers portraits are clusters of photographs, pinned, unframed, to the ICA walls. Without glass between us and his Greek subjects, we feel close to them. They look back as we move our eyes from their faces to their collections of hats and shells, to their artwork and shadows, to windows letting in the warm Greek light that characterizes his photographs.

Yorgos Efthymiadis, Costas T from The Lighthouse Keepers, 2024. Image by Yorgos Efthymiadis.

Costas T was “like the mother of the village,” Efthymiadis told me. The images of the land around Costa’s house are from three seasons, showing the passage of time. In Maria P, his aunt sits in her bedroom, before photographs of her wedding day. Her sorrowful expression hints at why the bed has only one pillow. She has recently lost her husband and now lives alone. The subjects of The Lighthouse Keepers helped Efthymiadis back to his homeland, showing him he still belonged.

Installation view of Yorgos Efthymiadis’ gallery, 2025 James and AudreyFoster Prize, the Institute of ContemporaryArt/Boston, 2025-26. Photo by Mel Taing.

Efthymiadis began The First Ones in Line in 2024. His partner is a labor organizer with Unite Here, a hotel and food service worker’s union. Knowing these “irascible, brilliant and charismatic” members, the artist set out to create portraits that would reveal their humanity. In their homes, often with family, we see them in their vulnerability. They are home after working, rallying, standing up for themselves.

Yorgos Efthymiadis, Sonia, Kylie, Dani. From the series The First Ones In Line, 2025. Inkjet print 20 × 30 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Amal stands in a shadowy doorway, her hijab obscuring everything except her resigned expression. Constantina sits tall on an ornate couch, images of Martin Luther King and Amilcar Cabral on the wall behind her. In Sonia, Kylie, Dani (2025) we get a blunt picture of what’s at stake. “I seek workers who, instead of retreating, decide now, more than ever, that they must be out in front,” Efthymiadis explained. “They are "The First Ones In Line."

Damien Hoar de Galvan

Damien Hoar de Galvan. Portrait by Yorgos Efthymiadis. Image courtesy of the ICA Boston.

“The world would be better if more people were making instead of destroying.”

Damien Hoar de Galvan creates artwork made of reclaimed wood, household detritus, paint and glue. His Foster Prize exhibition is an open gallery grounded by a site-specific “bench/bookcase” entitled Thank You that holds 51 artist books by the artists who have most inspired his decades-long creative practice.

Damien Hoar de Galvan, Nature vs. Nurture 2025. Acrylic, spray paint, ink, colored pencil, wood, glue, and screws. 17×13×5 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Working in the tradition of artists like Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Tuttle, who explored a space between painting and sculpture, the Milton-based artist fuels his practice with discipline, imagination, and modernist creative thought.

As much as any of the artists in the show, Hoar de Galvan’s Foster Prize room acknowledges the shared anxiety of our current moment by answering it with unapologetic trust in the artistic impulse: namely experimentation and individual expression. If our human state is at its core creative, and if that creative impulse can push back against seemingly insurmountable forces of political division and capitalistic greed, then we may well be saved.

Like the assemblage artists he studies, Hoar de Galvan imbues his work with surprise and humor. Completed works like Ride into the Sun and Slow Education transcend their salvaged physical materials and let the viewer delight in what they might mean. But don’t let the fact that Goya spice bottles and dirty toothbrushes find their way into his sculptures fool you into thinking they are naive or childish. Such intricate abstract layers and shapes require technical precision.

The heart of Hoar de Galvan’s exhibition is a display of the sculpture-a-day series the artist completed over the 2024 calendar year. Bachi Haas worked closely with the artist and the ICA exhibition team to find the best way to display the massive series. The result, five long shelves covering two walls, makes for joyful viewing. Walking into the gallery is like approaching a cage full of beautiful birds greeting you with fanned feathers. The sculptures are displayed in chronological order, making it possible to locate the one made on say, your birthday, or the day you quit your job, or the time you met your celebrity crush.

“I put my dirty toothbrush in a museum. That’s pretty cool.”

Sneha Shrestha (aka IMAGINE)

Sneha Shrestha (aka IMAGINE). Portrait by Yorgos Efthymiadis. Courtesy the ICA Boston.

“I wanted to disrupt the [gallery’s] boxy feeling. I wanted to create a world in there.”

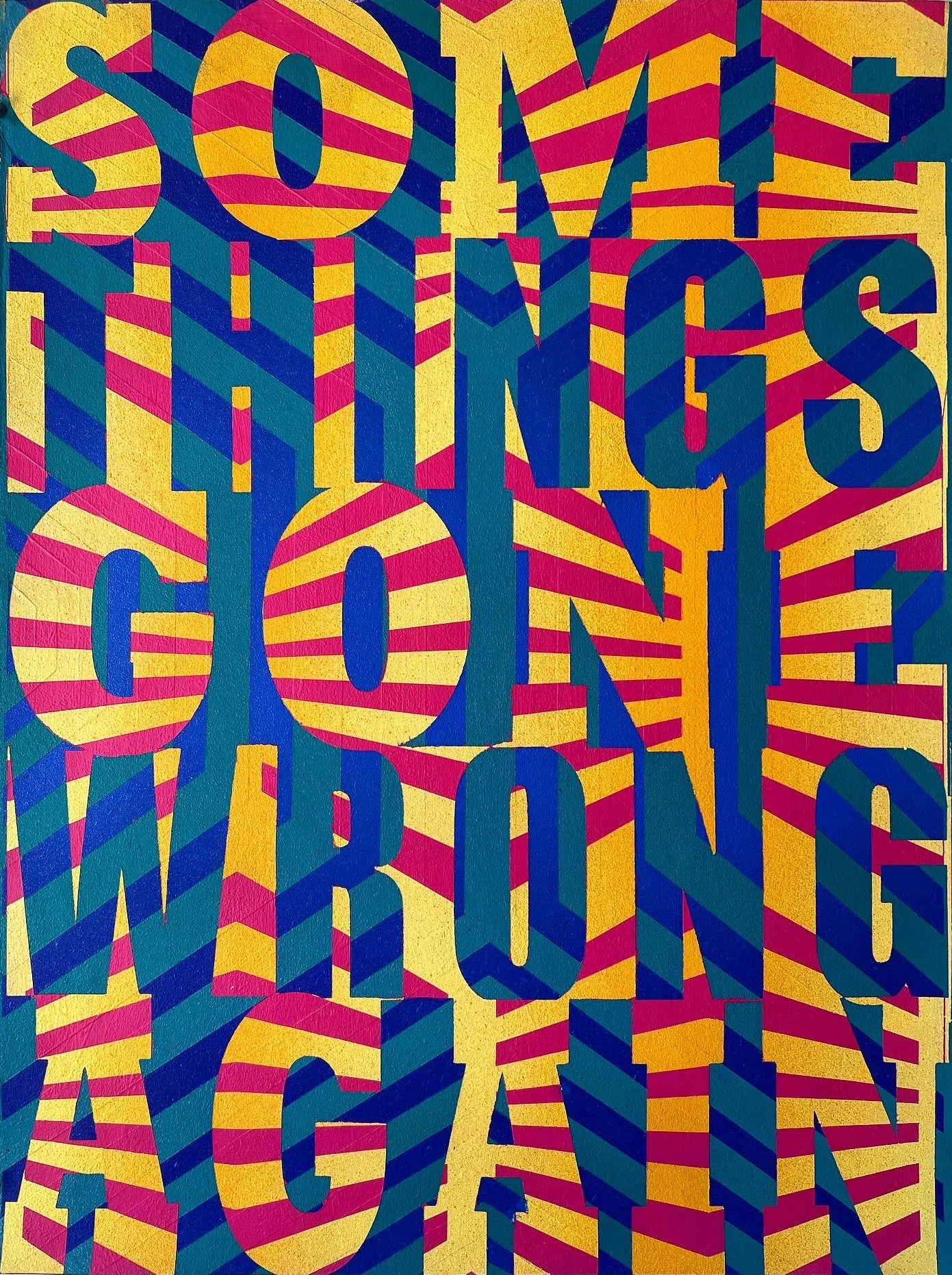

With a towering mural, a pair of seven-foot arches, luminous canvases stacked like windows, and a fabric-ringed sculpture evoking a ceremonial umbrella, Nepali-born artist Sneha Shrestha transformed her Foster Prize gallery from a white cube into an architecturally disruptive temple. Her recognizable visual vocabulary reimagines her native Devanagari script through a contemporary lens of graffiti, meditative repetition, and a sacred Tibetan color palette.

Shrestha grew up in Kathmandu where her family and childhood friends still live. She moved to the states to study at Harvard, and began painting public murals under the tutelage of Artists for Humanity’s Rob “ProBlack” Gibbs, adopting the name IMAGINE. Her public murals can be seen in Cambridge, East Boston, Fenway, and other areas in and around Boston.

At only thirty eight, Shrestha has achieved remarkable success. Her painting Home416 (2020) was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, making her the first contemporary Nepali artist in their permanent collection. Her sculpture Dwarpalika was recently acquired by Harvard Art Museums and will be on long-term view from December 2025. And in 2013 she was awarded an Advancing Leaders Fellowship from World Learning for her role in founding the Children’s Art Museum of Nepal.

Installation view of Sneha Shrestha’s gallery, 2025 James and Audrey Foster Prize, the Institute of ContemporaryArt/Boston, 2025-26. Photo by Mel Taing

Sneha Shrestha Way Home: Friends, 2025. Acrylic on canvas. 7 × 5 feet. Photo: Robin Hauck.

The Foster Prize mural mimics her orange and blue diptych Worlds Apart (2023) and addresses the oft-described immigrant condition of being of two worlds. The site specific installation was painted in the museum, the smooth gallery walls creating a different type of challenge than the textured exterior walls of the multi-story buildings she has painted around the world.

The arch paintings, Way Home Friends and Way Home Family are meant to evoke portals to home. As the artist explained, “Home for me is my friends and family.” This sentiment also comes through in her Celebration series, where Shrestha transcribed the names of the immigration forms she completed on her path to citizenship. The palette for each canvas was drawn from the clothing her mother wore to family celebrations in Nepal—occasions the artist missed while building her life in Boston.

“I want to make people feel like there is a place for their stories,” the artist said of her approach. “When the world is so unstable, we need family and friends more than ever.”

The James and Audrey Foster Prize exhibition will be on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston through January 19, 2025.