Inaugural Wagner Art Fellows Daniela Rivera & L'Merchie Frazier Prove Print is the Medium of Protest

Awards available to Boston-area artists address a myriad of needs and career stages. The Boston Foundation’s Brother Thomas Fellow’s Program, the ICA’s James and Audrey Foster Prize, the deCordova’s Rappaport Prize and Artadia’s Boston Awards, to name the biggies, provide vital support. They give local artists a national platform, introduce them to other working artists at the top of their game, and often make it possible to remain in Boston despite rising costs.

This year, Cambridge-based Wagner Foundation announced the Wagner Arts Fellowship, an annual award honoring three mid-career artists whose work centers cultural discourse and social change. This fellowship offers artists unrestricted grants of $75,000, as well as wraparound support services.

“To be in the well with these two masters of resistance and storytelling is very important to me… I am very grateful to those who have vision, who know how important supporting an artist’s work is, because this country does not honor art the way it honors other professions.”

Abigail Satinsky, Wagner’s Program Officer and Curator, oversees the Fellowship. She finds that artists have lots of different approaches when it comes to social change. “They can do it through studio practice or public art practice, activist practice, or socially-engaged practice.”

She worked with United States Artists, founded by leaders of the Ford, Rockefeller, Rasmuson, and Prudential Foundations, to identify the Wagner’s inaugural cohort: visual artist and public historian L’Merchie Frazier, visual artist Daniela Rivera, and painter and sculptor Wen-ti Tsen.

You can see the Wagner Art Fellows work in a free exhibition, Generations, at MAAM, the MassArt Art Museum, through November 30.

As part of the effort to raise awareness of awardees’ work, Wagner partnered with newly-launched Caira Art Editions to offer fellows the chance to create prints which will be exhibited and sold by Caira’s founder Lucy Rosenburgh. With her extensive knowledge of print and the New England art scene, Rosenburgh guides artists through choice of print process, print studio, and even subject matter. In this way, artists get a chance to experiment, deepen their practice, and ultimately share their work more widely.

You can explore Caira’s catalogue of available prints here, including works by Frazier and Rivera.

L’Merchie Frazier, Who’s In My Neighborhood? 2018, included in Generations at MAAM. Photo credit: Halsey McKay Gallery and L’Merchie Frazier.

I caught up with L’Merchie Frazier and Daniela Rivera to learn about their experiences translating their three-dimensional practices into print. Born in Santiago Chile, Rivera creates large-scale artistic interventions using vernacular materials such as adobe, lime and copper to confront political and personal histories of Chile and Latin America. She is a professor of Latin American studies at Wellesley and has exhibited around the world. Frazier is an artist, educator, and activist who uses quilting, collage, photography, teaching and poetry to address erasure and omission in representations of Black American history. She is a professor at MIT and an Executive Director at SPOKE Art. Though their work is very different, Rivera and Frazier’s practices have deep thematic parallels. Both artists provoke public memory, using their work to rescue unheralded stories and figures from obscurity. Both confront historical moments in which oppressive systems caused generational harm. And each artist incorporates culturally symbolic materials to charge their work with layered meanings.

For all these reasons, turning to print was both exciting and daunting for these veteran artists.

Daniela Rivera: Punto de Encuentro and She Never Kicked the Ball

Daniela Rivera, Punto de Encuentro (day 14). 2025. Etching with lime and pigment powder monotype, signed in pencil and dated, titled, variable edition of 20 printed by Stone Hill Press, published for the Wagner Foundation by Caira Art Editions on Magnani Pescia Soft White paper. Plate: 18 x 23 3/4 in., sheet: 22 x 30 in. ©Daniela Rivera, courtesy of the artist and Caira Art Editions. Photo Credit: Will Howcroft.

RH: Your practice involves complex, large scale installation, performance and sculpture, what made you say yes when Lucy Rosenburgh offered the print opportunity with Caira Art Editions?

“Materials are really important. I feel like they have more meaning sometimes than the actual thing that I make. The process that I’m using, and how the material informed the piece is really important to me. ”

DR: I want to figure out how to solve problems through the media, through the material. There's this beautiful thing of working with an expert, but also coming from left field, going against the tradition of the media. Working with the expert to figure how to solve a problem, that is a creative practice I just love. I mean, if I could spend my whole life, I would just do that and nothing else.

RH: Did you come to the subject matter on your own or did that come about as a result of conversations with Lucy or Brian [Smith, master printer of Stone Hill Press]?

DR: The soccer print She Never Kicked the Ball was the easiest. We got there fast because the project came through the process. When we started looking at the ball that I had been using for all of these drawings, I would say, ‘I killed it.’ It was covered with malachite and copper, and it had cracks. The surfaces were like topography—traces of its use, where it had been and what it's done. And so [I unstitched it and took it apart]… it became the death mask of the project. It was a beautiful way of finishing.

RH: The story behind She Never Kicked the Ball is fascinating and aligns with your video Ella Nunca Chuteo la Pelota (She Never Kicked the Ball) (2021). Can you tell me about what you learned when you interviewed women working in the Chuquicamata copper mine back in 2016?

Daniela Rivera considers the unstitched soccer ball at Stone Hill Press. Photo Credit: Caira Art Editions.

DR: The project started with the story of these women [of the Chilean mining town Chuquicamata] that organized around the men’s soccer team Cobreloa and got political representation. I started making these super beautiful renderings of a soccer ball made with a copper point. [In the print studio] I started bouncing the ball with all of these [copper] pigments: malachite and azurite, metal pigments that are blue and greenish. When Lucy came to the studio to see the drawings, our idea was to have a soft ground where we could bounce the ball, and leave the imprint of that bounce. We tried it, we failed. We tried it multiple times, we failed dramatically, to the point that we were going to abandon the idea, because, there's a budget, and a time limit. And I was like, no, I don't want to abandon this idea, and then I was like, let's just destroy the ball. I mean, the ball is already destroyed, so I unstitched the ball.

Daniela Rivera, She Never Kicked the Ball, 2025. Etching with copper leaf, signed in pencil and dated, numbered, edition of 10, printed by Stone Hill Press, published for the Wagner Foundation by Caira Art Editions on Hahnemühle Bright White paper. Plate: 11 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. Sheet: 18 1/2 x 18 in. ©Daniela Rivera, courtesy of the artist and Caira Art Editions. Photo Credit: Will Howcroft.

RH: And how about the monuments works, Punto de Encuentro?

DR: With Punto de Encuentro, I had been working with this idea of the monument since 2019. I started collecting imagery, data, architectural plans. [I was] trying to find archival material, from sound to images to video. I had all of this information, but I didn't know how to work it out. And it was in conversation with Lucy [that we said] ‘let's try to make it work.’ That was scary because I wasn't sure. I kept saying, ‘I am not an image maker. I am not good with images.’ The root of my practice usually turns into spaces, so I was freaking out that I was not going to end up with a strong image, because even though it is a space, and about a space, it's also representation.

Master Printer Bryan Smith and Daniela Rivera working at Stone Hill Press. Photo Credit: Caira Art Editions.

RH: Did you feel the monument idea was influenced by monument destructions and contests occurring globally? Not just in the US over Confederate statues, but also in places like the UK, Belgium, South Africa, and Taiwan over figures associated with slavery, colonialism, and dictatorship?

DR: Of course. This is based on a particular monument, but it's a symptom repeated all over the globe. This monument has history that precedes the Spanish colonization in Chile. The Incas went through this path, and there was a lot of Indigenous exchange. It's been a center of energy and the place for the majority of congregations in the capital Santiago, for [everything from] celebrating winning a soccer game to starting a protest against the government. It's a monument for General [Manuel Baquedano] who is partly responsible for Chile getting access to the territory that has the most of the copper [in Chile, the largest copper producer in the world]. And with the social explosion of 2019… it recontextualized my work in many ways. Every Friday [the monument] was defaced anew. I was fascinated by that, because I thought, this is even better than dismantling or demolishing.

Daniela Rivera, Punto de Encuentro (day 7). 2025. Etching with lime and pigment powder monotype, signed in pencil and dated, titled, variable edition of 20 printed by Stone Hill Press, published for the Wagner Foundation by Caira Art Editions on Magnani Pescia Soft White paper. Plate: 18 x 23 3/4 in., sheet: 22 x 30 in. ©Daniela Rivera, courtesy of the artist and Caira Art Editions. Photo Credit: Will Howcroft.

RH: Can you talk about the use of the tilted horizon line in Punto de Encuentro?

DR: This is something that I constantly use in my practice as a sign for the impossibility of arrival and the instability of place… it fits perfectly with everything that I'm talking about in the print.

“I think Lucy’s excited to work with people that are not necessarily working within the print world because we come with these things that are completely foreign, And maybe not totally orthodox to the practice itself.”

So this print is really important for me. [It incorporates] multiple things that happen in my practice: the research on copper, the implications of copper in the political history of the country, the extractive industry and how it's affected the whole world, every single life is affected by it. Then this idea of reconstructing history and [its material foundations.]

RH: With your use of lime and copper, you really pushed the printmaking into new territories. And that’s not even mentioning the soccer ball!

DR: [We used] different types of materials that are outside of the print world, which have to do with ancestral practices from Latin America. The lime has all of these implications. It's part of the colonial tradition. Lime was used in Chile for covering Adobe, for sanitation, it's part of Latin American life. Mexico uses lime for everything. We bury bodies with lime. We eat this food-graded lime. (Lime is the primary binder in fresco.) Fresco is linked to revolutionary practices and dispersion of information…Fresco practices were supposed to educate the people, from the dissemination of religious ideology to the Mexican Revolution… [engaging with this tradition of] critique on history was super interesting, with a material that has its own history.

L’Merchie Frazier: We Just Keep On Coming: 1706, 1965, 1968, 2020, 2025

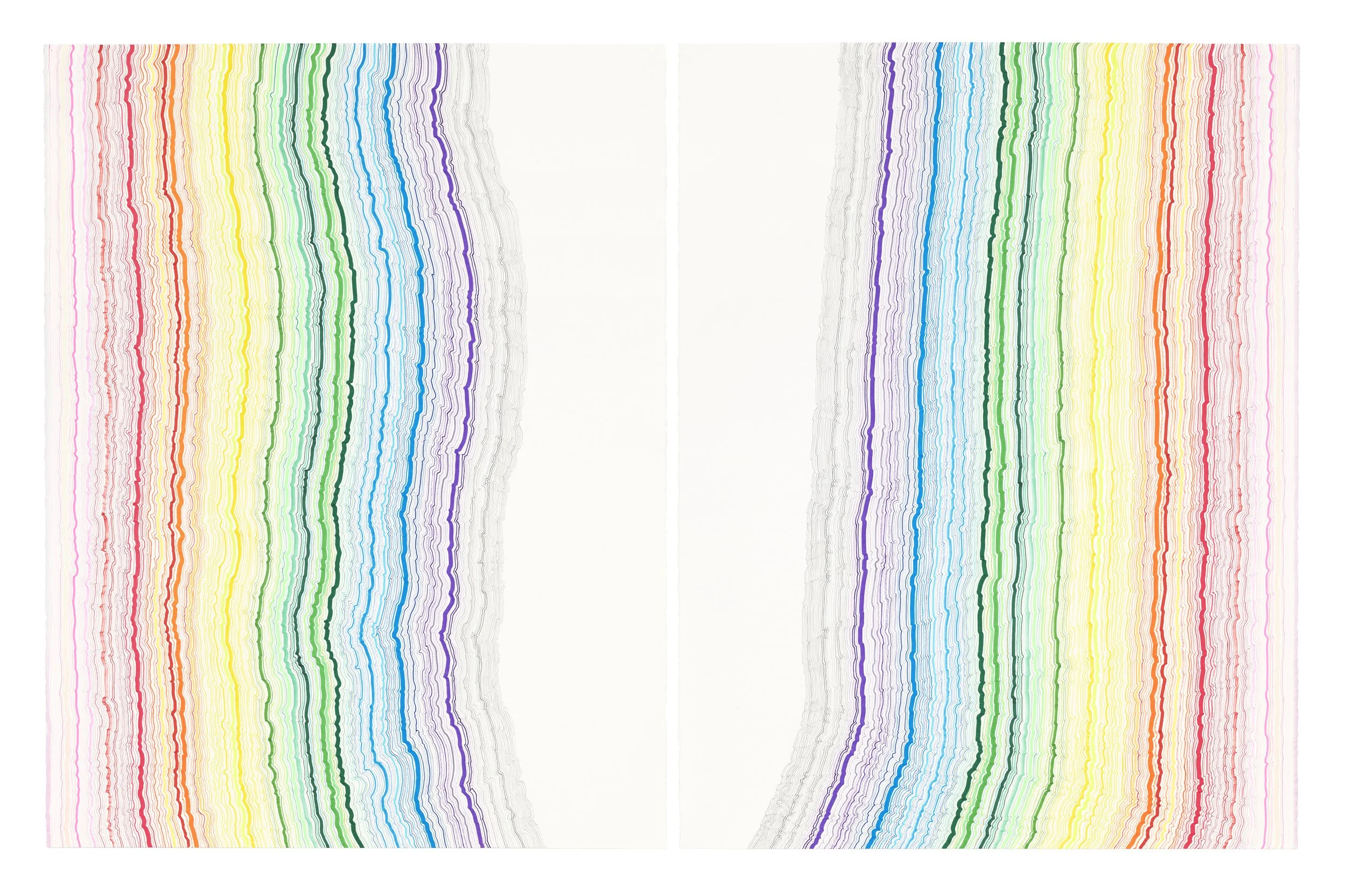

L’Merchie Frazier, We Just Keep On Coming: 1706, 1965, 1968, 2020, 2025. Screenprint in colors, signed in pencil and dated, numbered, edition of 30. Printed by Shepherd & Maudsleigh Studio, published for the Wagner Foundation by Caira Art Editions on Stonehenge Cream paper, sheet: 22 x 30 in. ©L’Merchie Frazier, courtesy of the artist and Caira Art Editions. Photo Credit: Will Howcroft

RH: You are part of the MLK Visiting Scholars and Professors Program at MIT, you’re currently teaching with Karilyn Crockett on the Hacking the Archives project in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, you worked for over twenty years at the Museum of African American History, and you help run SPOKE Art. Archival research is obviously a central driver of your practice.

LM: This visual document is where my art rests. It is chronicling selected events, people, places, times in history to provoke and make conscious these instances. To lead to the possibilities of what is not discussed institutionally in our education. These spaces that could have been better structured have not been structured, have neglected to answer questions. Maybe it is the artists’ way of fusing institutional education with community education, with alternative ways of seeing, to create this more accurate and expanded lens.

RH: Tell me about the way your print We Just Keep On Coming charts a path through history with all it’s layers.

LF: It’s called We Just Keep On Coming and When Will the Ground Stop Shaking? It begins with a document in 1706 and arcs to the current day, because the ground has not stopped shaking. We still are people moving and asking for civil rights. The particular landscape we are in today is demonstrative with all the protests that have been happening, of the ground still having to shake.

1706 is where my print is anchored, with an essay by Cotton Mather (The Negro Christianized) about the duty of the enslavers to Christianize the negro. That they felt it was their duty to offer Christianity for the salvation of the people they were enslaving is ironic, a heralding of the division between what is just and what is unjust, who is in authority and power.

Without this kind of information, we cannot face the ills of what is disruptive in America.

Printer Megan Cascella and L’Merchie Frazier at work screenprinting at Shepherd & Maudsleigh Studio. Photo Credit: Caira Art Editions.

As we take a journey through the print, go to the sign that is part of a newspaper illustration of Roberts vs City of Boston (used by other courts as precedent to justify racial segregation for nearly a century). Jim Crow legislation in education was here first. That for me is an important moment of ground shaking. Then we go to the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. They are carrying the banner of the American flag and the ground is shaking. That leads to the Poor People’s March, 1968, the year where Malcolm X gets assassinated, the Sanitation Worker’s Strike, I am a MAN, and the assassination of MLK.

We progress to Black Lives Matter in 2020 with that little sign that’s there - it’s all very subtle. But the radiation of the space, that blue area, those concentric circles, create that moire effect—of water, of sky, of target, of experimentation, of all of those activities that lead us to this mapping of movement. And the ground is still shaking.

Printer Megan Cascella and L’Merchie Frazier at work screenprinting at Shepherd & Maudsleigh Studio. Photo Credit: Caira Art Editions.

RH: The moire effect you and Megan Cascella created with the screen print gives the piece so much movement. It makes me feel that the protests of the past are the protests of now, that time is not linear.

LF: So the latitudinal and longitudinal lines that may be evoked in the imagination of this print are to talk about the global-ness of the movement embodied in the experience of the black diasporic happenings. That print for me as an important statement of widening our narrative of connecting dots that don’t normally get connected so that we can see better.

“The opportunity to do this print gave me another stretch, not only of vocabulary, but of my voice that resonates through all my work, whether it’s printing, poetry, fiber work, holograms or jewelry. All those mediums carry my voice with my moniker: remember, reclaim, restore, reimagine.”

RH: What does the Wagner Fellowship mean to you and your career?

LF: First, the honor of the cohort. To be in the well with these two masters of resistance and storytelling is very important to me. The promise of the money is to be able to breathe. To expand my practice, to have the time to investigate, to become larger in my sense of being human. I will be able to travel. We are not all privy to benefactors. I can create a legacy for people who haven't had that. Wagner also allows me to honor my grandfather James R. Dooley and my mother Theresa Dooley Frazier, a needleworker, and the legacy of craft and discipline that was passed down to me.